Our post today comes from Richard V. Denenberg, an author and journalist who has written about travel in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific region. Educated at Cornell, Stanford, and Cambridge Universities, he formerly served as an editor on the staff of the New York Times Week in Review section. He is the recipient of fellowships and grants from the English-Speaking Union, the Ford Foundation, the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

By Richard V. Denenberg

The vivid portrayal of a curmudgeonly butler and his well-drilled underlings in television’s “Downton Abbey” has shed sympathetic light on the vanished world of English country house servants. Fortunately for those whose curiosity was piqued, the vestiges of that shadowy realm of footmen, scullions, and valets have been painstakingly preserved by the National Trust.

Although the trust’s baronial dwellings have long epitomized the glamor of aristocracy, the plebeian precincts are shown as proudly as the haughty haunts of the landed gentry. A visit to the functional side of the grand estates evokes admiration for the silent corps of live-in helpers who swept the pastel drawing rooms, plumped the pillows on the canopied beds, and straightened the ancestors’ portraits.

The workaday rooms retain outstanding collections of copper and pewter utensils, brewing vats and cast-iron ranges, as well as a curious assortment of appliances powered by animals, humans or primitive hydraulics. In these utilitarian surroundings, you readily imagine Downton’s domestic crew feverishly preparing the hunt breakfast for red-coated riders.

The Edwardian butler was often an aloof major-domo who kept a steely eye on the staff as they served his lordship dinner from silver salvers. Yet a butler of some sort has been around for centuries and in earlier times was a fairly humble figure, according to historian Mark Girouard, an authority on country house life. Known as the yeoman of the buttery and classified as a “lower servant,” he reported to the clerk of the kitchen. (Although the term “buttery” calls to mind milk cans and churns, it refers to a storeroom for “butts,” or kegs, of ale.)

The habitat of the proto-butler can be seen to good effect in Derbyshire at Hardwick Hall, a flamboyant “prodigy house” of the Elizabethan era. Six symmetrically spaced towers rise above the roof line, framing a dazzling array of large, multi-pane windows, glinting in the sun. “Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall,” marveled an old ditty. Only a determined squeegee squad could assure the noble inhabitants a clear view of the herb garden.

Feeding the grandees was also a herculean task. Hardwick’s mistress, the well-connected Countess Bess, often entertained as many as 300 house guests. By modern standards, their need for nourishment was daunting. In a single gluttonous week between Christmas and New Year’s Day, the celebrants quaffed 17 hogsheads (918 gallons) of beer and ale, washing down 180 “muttons,” 51 “veals,” ten turkeys and 1,500 eggs. Vast quantities of food and drink were borne in formal procession up to the tapestry-hung High Great Chamber, where diners gazed upon vibrant scenes from “The Odyssey,” woven in Brussels.

Treading the shallow stone staircase, which meanders through the floors like a corniche road, one visualizes the train of bearers, ascending with their trays and flagons. The landings are noticeably broad: they did double duty as a dormitory and ready room for servants, who awaited the countess’s call round the clock. Separate service stairs had not yet appeared, nor had such refinements as the call button or bell rope.

The Great Kitchen, where the feasts originated, is still in working order. A high ceiling rests on stout, octagonal columns, encircled by rough-hewn oak drop leaves with ponderous balusters for feet. The bare planks would have been a natural place to lay out refreshments when stair climbing whetted appetite.

Copper cooking implements gleam atop a bank of charcoal-burning stoves—the forerunner of the kitchen range. The batterie de cuisine comprises scores of skillets, roasting pans, kettles and ewers. They are complemented by pewter platters, arrayed in a diamond pattern on the wall.

A notable collection of copper also graces the kitchen of Charlecote Park, another 16th-century mansion, situated on a languid bend of the River Avon, upstream from Stratford. (As a youth, Shakespeare was arrested there for poaching game.) The kitchen has been restored to its mid-19th-century appearance. An eye-catching piece is the multiple bain-marie, a constellation of dainty pots immersed in a larger vessel, allowing several sauces to be heated simultaneously.

The elegant culinary apparatus contrasts starkly with a rugged artifact of the Industrial Revolution—a mighty coal-burning stove of black iron. Boasting the name of Grove’s Prize Kitchener, this 1850 model had been cast at a nearby foundry and set into an arched brick recess. The twin double-doored fireboxes, decorated with finely wrought strap hinges, seem capable of generating enough steam to propel an ocean liner.

Also on display are antique molds and balance scales, sugar cone nippers, and a heavy-duty mortar, cradling a pestle reminiscent of a Polynesian war club. A large window, positioned high in the end wall, provided light without permitting the staff to be distracted by the sumptuous landscaping.

Liberated from the landings, Charlecote’s servants slept in the attic. A set of brass bells summoned attendants from the kitchen to the dining room, library or “bachelor’s room” (perhaps intended for unmarried guests). Gouges in the floor of the “servants’ hall,” which became a book shop, show where the gardener supped in his hobnail boots.

As the origin of the butler’s office suggests, beer once was as vital to country houses as solid food. Each was supplied by its own microbrewery, often situated in a separate building or a service court. The detached brew house at Charlecote retains an intricate cascade of boilers, lead-lined vats and wooden tubs for infusing barley malt, fermenting the mixture and filtering it. The equipment survives in such pristine condition that the custodians have dreamed of firing it up again to produce a distinctive home brew for sale. (More sober thoughts ultimately prevailed.)

A contrasting arrangement is found at Canons Ashby House, which has nestled among Northamptonshire sheep pastures since the 1550s. Its brewers occupied a quadrangular beehive of domestic industry—the Pebble Court—which also sheltered a laundry, bakery, and dairy.

Wide view of the Kitchen at Canons Ashby showing the range door, servants’ bells and wooden tables. The stone-flagged Kitchen remains the same shape as that of the original Tudor manor house. National Trust Images

Although consigned to mundane pursuits, the Pebble Court became the main entrance to the house. Why this humble enclosure should have been so favored is not difficult to fathom. Attractively paved with a tight pattern of irregular cobbles, the court is bounded by lichen-dappled walls of russet stone. One wall belongs to the Great Hall, where the servants kept busy polishing an arsenal of heirloom weaponry—daggers, halberds, and a specialized implement listed in the inventory as “knife for decapitation.”

Besides the hall, there was a drawing room to be tidied. Suspended from its domed ceiling—studded with plasterwork pomegranates and thistles—is a particularly labor-intensive feature: an elaborately carved stalactite that must have been wickedly difficult to dust before the advent of vacuuming.

Obtaining water often required ingenuity. At Canons Ashby, hollowed tree trunks linked end to end served as water mains, connecting to a medieval well across the road. At another estate, hilly Greys Court in Oxfordshire, servants in the Tudor reign had to dig by hand a well 200-feet deep and devise a sort of treadmill: a donkey plodding inside a cage-like wheel hoisted buckets of water. The beast has gone, but the wheel is still there, overlooked by 14th-century fortifications.

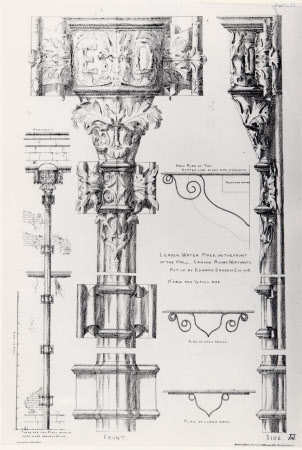

Illustration from “Spring Gardens Sketch Book”, Leaden Water Pipes on the front of the Hall, Canons Ashby, Northants – National Trust Images

By the Victorian period, labor-saving devices had reduced the drudgery of many great households. Perhaps the most advanced was Cragside, a dreamy confection of tall chimneys and half-timbered gables, crowning a Northumbrian peak. It was built, largely in the 1870s, by William, Lord Armstrong, a munitions magnate who personified the military-industrial complex at Britain’s imperial zenith. (He may have been a model for the cynical war profiteer, Andrew Undershaft, in George Bernard Shaw’s classic play, “Major Barbara.”)

As a tycoon’s outré retreat, Cragside prefigured by half a century the Hispano-Moorish extravaganza erected by William Randolph Hearst in the hills above San Simeon, California. Both Williams made their fortunes from international conflict, one by provoking it, the other by supplying the ordnance. But Armstrong brought something home from the arms race: a passion for invention.

Harnessing the estate’s streams and man-made lakes, he introduced two power sources—hydro-electric and hydraulic—that were unknown in domestic settings. Cragside was illuminated by incandescent bulbs; all switched on at the same time, like a string of Christmas tree lights. Thanks to hydraulics, an elevator helped the cooks raise cast-iron cauldrons from the scullery to the glazed-brick kitchen, and a spit large enough to rotisserie an ox turned robotically before an open fire. A loop trail affords an overview of this ingenious technology.

The double-story chimneypiece surmounting the inglenook in the Drawing Room at Cragside, made of Italian Marble. National Trust Images

Despite his fascination with engineering, Armstrong enjoyed old-fashioned, if outsize, creature comforts. At Cragside, the traditional inglenook, a cozy fireplace alcove, became an intricately carved, 10-ton proscenium arch, hewn from Italian marble. Furnished with paintings and leather settees, it resembles a stage set awaiting the actors.

For the cleaning staff, though, it must have been a grim spectacle indeed, much like the ceiling pendant at Canons Ashby. The Cragside inglenook is the Mount Everest of mantle pieces, collecting dust the way the Himalayas collect snow. Still in the household is the two-story ladder on which servants perched while scrubbing particulate matter from Cupid knees and angel wings.

Canons Ashby Drawing Room ceiling, close view to pendant boss and painted coat-of-arms. National Trust Images

The English country house tradition found its way across the border into Wales. Near Wrexham, in the north of the principality, the long, two-story façade of Erddig Hall (pronounced ERTH-ig) and its 1,200-acre park dominate the valley of the sinuous River Clywedog. The late 17th-century edifice is known for its collection of fine furniture—and its owners’ affection for their dedicated servants.

Rather than being admitted through the formal front door, visitors are led to venerable outbuildings where the heavy labor of running a large agricultural enterprise was performed. Carpentry and blacksmith shops join a steam-powered saw mill and stables for the sturdy “shire” horses that hauled logs from the nearby woods.

Over many generations, the heirs to the house—a family of earls—showed uncommonly deep appreciation for the workers involved in these onerous duties. Below a panel of call buttons is a poem that seeks heavenly protection for those “who bestow their toil on this estate.” The heirs also acted as matchmakers, solemnizing the marriage of a nanny and a groom with a prayer that “love, to ours so freely shown, be spent on children of their own.” And at Erddig the portraits are not only of the ancestors. The faces of the loyal retainers hang by their side, demonstrating that the earls were no churls.