Join us on a journey through England with curator Richard V. Denenberg as we discover an amazing country house interior created by William Morris. Mr. Denenberg is an author and journalist who has written widely about travel in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific region. Educated at Cornell, Stanford, and Cambridge Universities, he formerly served as an editor on the staff of the New York Times Week in Review section. He is the recipient of fellowships and grants from the Ford Foundation, the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

By Richard V. Denenberg

William Morris, the multi-talented Victorian visionary, died 120 years ago, an occasion that is being commemorated by spiritual heirs as diverse as social theorists and interior decorators. Many of those marking his achievements are likely to make pilgrimages to destinations in England linked to Morris’s dream of imbuing everyday life with beauty.

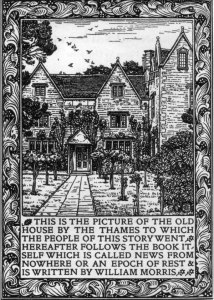

Two shrines in particular attract the pilgrims. One is Kelmscott Manor, a Cotswold farmstead where Morris spent his summers. A relic of the Elizabethan era, it has been described by a contemporary as “the resort of poets and artists, critics and connoisseurs, disciples and aspirants.” The second is Wightwick Manor (National Trust), an opulent West Midlands country house that epitomizes the Arts and Crafts Movement, an outgrowth of Morris’s reverence for traditional workmanship.

Kelmscott was an inspirational retreat for Morris, Wightwick (pronounced WIT-ick) a polished showcase for his virtuosity. At Wightwick, even visitors unfamiliar with the Morris legacy come to appreciate its significance for our own era—and often return home with ideas for refurbishing the living room.

Born in 1834, Morris was a one-man cultural force as well as an innovative entrepreneur. An ebullient, bearded figure—easily mistaken for a sea captain–he wrote utopian fiction, socialist tracts, and poetry, including a renowned epic, “The Earthly Paradise.” He unlocked for English readers the legends of early Norse adventurers and founded Kelmscott Press, whose volumes of lavish drawings and unique typefaces are prized by collectors.

Born in 1834, Morris was a one-man cultural force as well as an innovative entrepreneur. An ebullient, bearded figure—easily mistaken for a sea captain–he wrote utopian fiction, socialist tracts, and poetry, including a renowned epic, “The Earthly Paradise.” He unlocked for English readers the legends of early Norse adventurers and founded Kelmscott Press, whose volumes of lavish drawings and unique typefaces are prized by collectors.

Morris powerfully influenced taste in the fine as well as applied arts. He and his circle formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a school of painting that sought to reclaim the sincerity of early Italian art.

A back-to-the-future progressive, Morris spurned the “cheap and nasty” output of the machine age, seeking to recapture the esthetic sensibility of medieval masons, scribes and dye makers, who united style with utility. He expressed his disdain for mass production by creating imaginative, hand-woven tapestries and carpets, hand-printed textiles and wallpapers, and hand-cut woodblocks—all now regarded as classics of design. In addition, Morris produced sturdy wooden furniture, pleasing in its simplicity; these manifestations of the Arts and Crafts idiom were antecedents of the Stickley and Mission genres.

He also created a large array of vibrant chintz fabrics that honor the English landscape. A careful observer of nature, Morris named his patterns after quiet tributaries of the Thames, like the alliterative Windrush, Wandle and Wey, and reproduced the essence of hedges and fields (Blackthorn and Sunflower). As a colorist, Morris lived off the land, extracting dyes from common plants—yellow from poplar twigs, for example. As a result, the textiles seem “stained through and through with the juices of flowers,” in the words of W. R. Lethaby, one of his followers.

Today’s efforts to resuscitate the skills of artisans, conserve unspoiled countryside, and sensitively restore historic buildings owe much to his ideas. He denounced restorers who prefer “gilding, glitter and blankness” to the solemn effect of “hundreds of years of wind and weather.”

Morris was connected to Wightwick, about a two-hour drive to the north of Kelmscott, through the firm he founded to decorate the homes of forward-looking plutocrats. Morris & Company was in business from the 1860’s until World War II. The paradox of an anti-industrial philosopher adorning the mansions of industrialists was not lost on Morris. He expressed regret for the time he spent “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich.”

Wightwick was the flamboyant residence of Theodore Mander, a paint manufacturer who bought many of the original furnishings from Morris & Company. Built between 1887 and 1893, it is a fanciful pastiche of vernacular elements on a grand scale. Several varieties of black-and-white half-timbering—vertical, diagonal and clover-leaf—compete for attention under a red tile roof. Exuberant facades bulge with protruding bays, turrets and gables draped in pink wisteria and yellow climbing roses. Lofty brick chimneys, grouped around a crenelated tower, loom over delicately carved beams and Gothic tracery barge boards.

Although each feature is authentic, according to Stephen Ponder, an architectural historian, the ensemble is “just a little too good to be true, with rather more intricate and varied detail than would be found in any one genuine building.” Wightwick should be viewed as a paean to the past, an eclectic tribute to centuries of building with timber.

An oddly angled porch leads to the Entrance Hall and its gleaming, beaten-copper fireplace hood. Sunshine streams from a six-light stained glass window, studded with figures who personify such virtues as peace, joy and temperance. (The Manders were teetotalers.)

The family creatively mixed Morris-inspired decor with antiques from many continents: carpets from Central Asia and the Caucasus; chairs and tables of the English Jacobean, Restoration and Georgian periods; and brightly glazed ceramic urns and bowls from Japan and China. The collection is enriched by a veritable museum of Pre-Raphaelite painting and sketching.

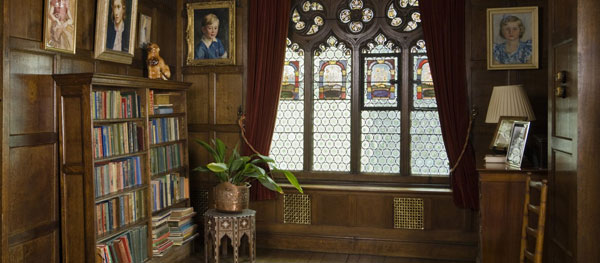

At the heart of the house is the Great Parlor, a sitting room with many attributes of a Tudor armorial hall. This two-story cavern of burnished oak, some of it retrieved from older houses, manages to seem livable, perhaps because the fireplace, inset with blue-and-white Dutch tiles, is enclosed in a cozy inglenook alcove.

At one end of the parlor, a balustraded gallery suitable for minstrels projects above the five-foot-wide gold frame of “Love Among the Ruins” (1894) by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, a member of the Brotherhood. A reflection on the endurance of love in contrast to the impermanence of worldly power, the oil painting portrays a young couple embracing among fallen classical columns overgrown with prickly brush. It was taken down and shipped to Washington D.C. to serve briefly as a centerpiece of the landmark “Treasure Houses of Britain” exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (1985-86). A watercolor version by the same artist sold for more than $22 million in 2013.

The parlor is a “Where’s Waldo?” of Morris designs. They are woven into panels of tightly stretched woolen cloth beneath the ceiling frieze (Diagonal Trail). They line and curtain the window bay (Acanthus and Tulip and Rose), and they cover the wing chair and sofa (Strawberry Thief and Bird). The exquisite upstairs bedrooms are named for the firm’s patterns, which decorate them.

Like the fabrics, the wallpapers were produced painstakingly and stamped with specially mixed pigments. Naturalistic and stylized flowers are ingeniously blended, as are curvilinear vines and geometrical trellises. Adding a three-dimensional effect to flat walls, the papers have a timeless appeal. Many are still in production.

Like the fabrics, the wallpapers were produced painstakingly and stamped with specially mixed pigments. Naturalistic and stylized flowers are ingeniously blended, as are curvilinear vines and geometrical trellises. Adding a three-dimensional effect to flat walls, the papers have a timeless appeal. Many are still in production.

There are numerous echoes of Kelmscott at Wightwick. A wicker chair that once belonged to Morris’s wife, Jane, enhances the Honeysuckle Room, and her portrait by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, another member of the Brotherhood, hangs in the Drawing Room. The plush Billiard Room, which offers spectators raised seating, is covered in the same wallpaper (Pimpernel) that embellished the Morris dining room.

Even the garden pays homage to the Morris home; many of its plants once grew at Kelmscott. Here they have formal company: an alley of giant yews, clipped into bulging drum-like shapes, and an orchard of ornamental crabapple and plum trees. The garden’s outline is irregular. In keeping with its asymmetrical character, Wightwick stands in one corner, allowing the 17 acres to sweep downward toward pools edged with billowy azaleas and filled with carp and trout. The view of the house from the bottom of the garden is ethereal.

Wightwick is three miles west of Wolverhampton via the A454.

At least four other National Trust sites are associated with Morris:

- Buscot Park, an 18th century mansion near Lechlade-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, houses the magnificent Burne-Jones series titled “Legend of Briar Rose” (1890). Four mammoth paintings narrate a fairy tale from the Middle Ages thought to be the origin of the Sleeping Beauty myth. A short distance away is Kelmscott, which is administered by the Society of Antiquaries of London.

- Standen House, set in a 12-acre hillside garden in Sussex, displays a considerable amount of Morris & Company furnishings in the relatively modest setting of a weekend home. It was completed in 1894 as a getaway for the family of a railroad lawyer.

- The Red House in London is where Morris lived from 1860 to 1865. A hidden mural on a biblical theme, possibly painted by Burne-Jones or Rossetti, has been discovered there.

- Quarry Bank Mill, a Cheshire cotton factory that opened in 1784, has woven Morris-designed fabric (Diagonal Trail), using power supplied by a water wheel.

Further Information

One of the largest exhibitions ever mounted at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was dedicated to the William Morris Centennial in 1996. More than 500 items were displayed and can be examined in the exhibition catalog. Many objects are in the museum’s permanent collection.

The Pierpont Morgan Library in Manhattan published an exhibition catalog the same year, titled “Being William Morris.” It contains 195 objects, including many of the designs found at Wightwick, along with Kelmscott Press books and medieval manuscripts once owned by Morris. A full-scale biography, “William Morris: A Life for Our Time” by Fiona MacCarthy, has been published by Knopf.