Love gifts from Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf and Harold Nicolson are among the items on display as Sissinghurst explores writer’s travels around Persia

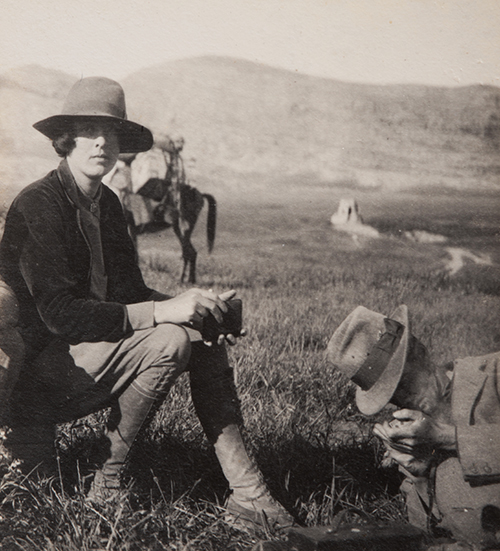

Vita at the plain of Malamir (now called Izeh), Iran © National Trust Images

The new exhibition will explore how travels to Persia, now modern-day Iran, in the 1920s inspired Vita and husband Harold in the design of Sissinghurst’s garden and interiors as well as their writing and relationships.

Objects and photographs – some of which have never been on public display before – from travels to Persia, now modern-day Iran, by writer Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicolson are the focus of a new exhibition opening on Saturday, October 14, at their former home, Sissinghurst Castle Garden in Kent.

Focusing on the period 1925 to 1927, “A Persian Paradise” will tell the story of how the region inspired Harold and Vita, from the design for Sissinghurst’s garden and interiors to their writing and personal relationships. The exhibition includes keepsakes and gifts from Vita to her lover Virginia Woolf that will be displayed together for the first time in nearly a century, along with photographs taken at various historic sites.

Vita and Harold were two of the most high-profile cultural figures of their generation. They wrote vividly about their experiences in the mid-1920s, their responses channelling a growing fascination for all things Persian. They witnessed a time of change as Persia became Iran and Vita’s travelogues in particular offer glimpses of this time.

The National Trust has led research into letters, diaries and other material with academic partners to examine in more detail the collections at Vita’s home Sissinghurst, and at Monk’s House in East Sussex, the home of her lover Virginia Woolf.

A highlight of the exhibition is the reunion of two pieces of stone from the ruins of the ancient palace of Persepolis, which Vita visited in 1927 – one piece of which was a gift to Harold and the other for Virginia. The significance of these pieces has very recently come to light during research for the exhibition.

The two pieces probably come from the beard of one of the Assyrian large-scale bull figures which flanked and guarded the columned portico of the Hundred Columned Hall at Persepolis and clearly show the whorls of hair from the beard.

Pieces of sculpture from the ancient palace of Persepolis, given by Vita Sackville-West to Harold Nicolson and Virginia Woolf ©National Trust Images/James Beck

They are believed to have already been in fragments when Vita and Harold found them at the site, however researchers are considering whether Vita may have cut one of the pieces in half. She treated them as keepsakes, and much like real locks of hair given to a beloved, they served as love tokens to Harold and Virginia. Vita kept a third, but different, fragment from another part of the Persepolis palace on her own desk.

However, Virginia’s fragment later came to represent the ruin of their relationship. In 1934, regretting that Vita no longer loved her, Virginia wrote describing “the piece of Persepolis”’ on her mantelpiece as “gathering dust.” Vita recalled it as “that paperweight” behind which Virginia kept her letters, or worse, a jumble of notes from rival romantic partners.

Also reunited for the first time since the 1920s, is a blue cog dish, bought by Vita in an assortment at a bazaar in Tehran and given to Virginia. Usually displayed at Monk’s House, it will be exhibited alongside similar dishes from the group kept in Vita’s Writing Room at Sissinghurst.

The exhibition includes a set of orange beads, given to Vita when she and Harold were invited to dine with the Il-Khan, the supreme chief of the Bakhtiari Tribe. She recalls “the string of corals with which he was playing, slipping the beads between his fingers as he talked, as all Persians do; it lies on my table as I write.” Until the research was carried out for this exhibition, the provenance and identity of the beads had been thought lost.

A string of coral prayer beads, given to Vita when she and Harold were invited to dine with the Il-Khan, the supreme chief of the Bakhtiari Tribe ©National Trust Images/James Beck

Vita and Harold’s personal photographs provide many glimpses of life and monuments in the 1920s that were transformed in the following decades. They photographed mounted tribesmen and migrating families whose way of life radically changed within a generation. Their many views of Persepolis show that they keenly explored the site before it was changed by excavation in 1931.

Photographs not displayed in public before include their time within the Tehran Embassy compound; from the Coronation of the Shah, the oilfields, and with colleagues and friends, including Raymond Mortimer – ‘Tray’ – Harold’s long-term lover, who went out and stayed with him for quite a while and who travelled with him and Vita with the Bakhtiari Tribe.

The atmosphere of the exhibition will be enhanced with scents from spices and perfumes and music, along with original film footage of sites in the region from the 1920s.

Nicci Obholzer, Senior House and Collections Officer at Sissinghurst Castle Garden said:

“Harold Nicolson was born to a diplomat father in Tehran in 1886. He returned there in the 1920s to work in the British embassy and Vita visited him twice. Vita immediately published two richly described travelogues of her trips there.

“A decade after Harold’s posting to Tehran, Persia officially became Iran in the languages of the world. A new king, Reza Shah, tried to reframe Iran’s relationship with the world. Vita and Harold experienced a diplomatic lifestyle at a time when British influence was still significant but beginning to decline. Their responses reflect these events.

“Both held a lifelong affection for the region and took many vivid photographs of people and sites. These are now a fascinating record of a country on the cusp of great change.

“It is poignant to see some of the objects from her travels that Vita gave to Virginia and to Harold which have been reunited for the first time since they were given. We hope visitors will enjoy finding out more about this period of the lives of two of the 20th century’s most eloquent observers and the new discoveries we have made about them that reflect the Sissinghurst we see today.”

For the exhibition research, the National Trust has worked with Kings College London, University College London, University of Cambridge and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

New Exhibit to Open at Sissinghurst

“A Persian Paradise” opens at Sissinghurst on Saturday, October 14 until March 24 and is generously supported by The British Institute of Persian Studies and the Iran Society.