Royal Oak’s Jan Lizza visited Penrhyn Castle, Wales more than 20 years ago, calling it a “fairy tale place.” Today’s Flashback Friday is part two of Jan’s reflection on her time at Penrhyn. Read part one here and then trace Jan’s footsteps with a trip to Wales of your own. Join Royal Oak today and enjoy unlimited access to National Trust properties across the United Kingdom. Join Now

Part Two

Penrhyn is astonishing not only in terms of its size, but also in terms of its contents and decor. I wandered through the house, listening intently to the recorded tour which directed my attention to each new point of interest, stopping to linger over a curious piece of carving, or appreciate the beauty and craftsmanship of an exceptionally fine piece of furniture. The hours passed as I made my way through this lovely and lavish labyrinth. My tiny studio apartment in New York would seem even more minuscule to me, I was certain, after my experience of the width and breadth of such spacious grandeur.

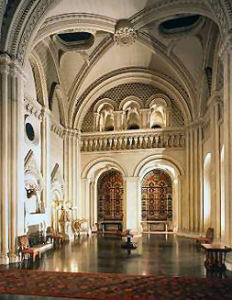

The intricate and imaginative carving which permeates almost every aspect of Penrhyn is extraordinary. The ceiling and the four great archways that dominate the Library are just two examples of this kind of craftsmanship. Indeed, I spent a good deal of my time that day gazing upward at many sculpted ceilings. But the piece de resistance has to be the Grand Staircase, the wildest achievement of the castle’s interiors. This is Hopper pulling out all stops; Hopper crashing through the mysterious veil that separates the conscious mind from the subconscious. The massive staircase is an orgy of fantastic carving depicting a magical kingdom populated by pixies, elves, bearded Vikings, and helmeted Inca warriors. A surreal world where serpents and dragons intertwine, and a cast-iron bowman’s arm reaches forth from a monstrous gaping mouth to hold up bronze oil lamps. Looking closely one discovers the ten hands that grace the archway of the door leading to the Drawing Room. A row of heads is sculpted round the cornice. Each bears a different expression: some laughably grotesque, others grinning wildly or angrily gnashing their teeth. This outrageousness is balanced with sculptured pillars, and minutely carved, interlacing arches. This monument to the imagination was 10 years in the making; and for this amazing work, the local stone-masons were paid 3 shillings (15 pence) per day. The Grand Staircase is certainly awesome, but it seems to me that every room at Penrhyn holds something special. There is the billiard table made entirely of highly polished enameled slate and the mammoth canopied bed carved of the same fragile material. 18th-century, hand-painted Chinese wall paper hangs in the State Bedroom; Queen Victoria, on her visit in 1859, slept here in the magnificently carved oak four-poster, surrounded by damask curtains.

I particularly liked the Drawing Room. Apparently, the original red and gold silk hangings, curtains and upholstery had deteriorated by the 1930’s to warrant their removal. And indeed, for the next 50 years the walls and ceiling were covered over with brown and white paint, and the sculpted woodwork was stripped of its polish. Then in the mid 1980’s the National Trust restored this room to its former glory: recreating the magic by copying original fragments of fabric which had survived. The once-dull brown walls are again aglow with red silk, and 2,000 hand-painted gold stars have returned to adorn the ceiling.

But why would anyone have chosen to paint over 2,000 gold stars to begin with? It seems that during the Second World War Penrhyn served as headquarters for the Daimler motor company. Certain rooms were used as administrative offices and typing pools, and it was believed that productivity would increase if the magnificence of the surroundings was toned down. And so, sculpted, wood grained, plaster ceilings, carved oak doors and a firmament of stars were white washed for the war effort.

Penrhyn also temporarily housed museum pieces during the war. In 1939 the National Gallery’s collection of Old Masters was evacuated from London to various sites in Wales. Penrhyn was chosen because it was one of the few buildings in Wales with doors large enough to admit the biggest of the paintings -Van Dyck’s equestrian portrait of Charles I. Paintings were stored in the Dining Room and two coach-houses. After the fall of France in 1940, the perceived threat of bombing increased, and the paintings were moved again to a slate mine at Blaenau Ffestiniog.

I had a nice chat with two of the stewards at Penrhyn: Doris Parry who was on duty in the Breakfast Room; and Gwynn Ellishughes, one of the Head Stewards. I enjoyed talking with them; their knowledge of Penrhyn and the history of its contents was prodigious. The stories they told of the challenges which the National Trust faced in restoring the castle (i.e. the delicate work of removing WWII paint and refinishing the very doors andceiling of the room in which we were standing) made me appreciate even more the artistry and beauty of the place. I wanted to go back and start at the beginning, so that I could see everything again with a more keen awareness of the monumental accomplishment achieved by the National Trust in its ongoing restoration and preservation of Penrhyn.

Next to the Breakfast Room is the Dining Room. This banqueting hall, like the rest of the castle, is grandiose in all its proportions. The huge veneered oak dining table by Hopper (constructed in four separate pieces) extends almost the full length of the room. It is surrounded by twenty ebony chairs upholstered in velvet. Massive buffets of carved oak, companion pieces to the dining table, stand guard along the walls. And although there is an eloquently carved black marble chimney piece in the room, I was most impressed by the bay of five arched windows that stand from floor to ceiling, and span the length of the eastward wall. These are luxuriously draped with voluminous, ruby red velvet curtains dating from the 1830’s. Extravagant in their overuse of material, which spills onto the floor in delicious velvety pools, these curtains are supported from above by a drapery pole that looks like the mast of a great seafaring vessel. It is the original pole and must be 60 feet; a magnificent place to have a dinner party!

At the far end of the room, there hangs a Dawkins family portrait; George Hay Dawkins, the builder of Penrhyn, is still a young man in this painting. However, his youth is not what strikes one first, indeed there are many other more noteworthy paintings throughout the house (of the 300 existing Rembrandt’s in the world today, one hangs in the Breakfast Room). What draws one’s attention to this particular picture is its immense size: 170 square feet of canvas. Just before leaving, I met one of the many recruiters that are so important to the Trust. Jill Williams was about to encourage me to join the roster of National Trust members when she learned that I was already a member of Royal Oak.

At the far end of the room, there hangs a Dawkins family portrait; George Hay Dawkins, the builder of Penrhyn, is still a young man in this painting. However, his youth is not what strikes one first, indeed there are many other more noteworthy paintings throughout the house (of the 300 existing Rembrandt’s in the world today, one hangs in the Breakfast Room). What draws one’s attention to this particular picture is its immense size: 170 square feet of canvas. Just before leaving, I met one of the many recruiters that are so important to the Trust. Jill Williams was about to encourage me to join the roster of National Trust members when she learned that I was already a member of Royal Oak.

When I told her that I was also a staff member of the Foundation, she bubbled over with excitement, finally being able to put a face to the organization that recruiters talk so much about to Americans. Here was a comrade-in-arms, so to speak, from across the Atlantic.

I, too, was pleased to have met some of the people that make up the vital fabric of the National Trust. My visit to Penrhyn will always be special, not only because I was able to wander through a unique world brought back to life by the vision and commitment of the National Trust and its many supporters; but also because of the friendly people who welcomed me so warmly into that fairy tale place called Penrhyn.

Don’t miss out on your own visit to Wales. Travel with Royal Oak this summer! Join Now