Republished with the permission of the National Trust.

This year the National Trust is celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), a national heroine known for her pioneering role in nursing

A life-long calling

Florence Nightingale on her mother’s knee, watercolour (c.1822)/©National Trust, John Hammond

Florence Nightingale was born in Florence, Italy, in 1820 to a wealthy English family. From a young age she harboured ambitions to become a nurse. She cared for the sick on her family’s estates and believed her godly calling in life was to reduce human suffering.

Florence’s family, however, were not supportive of her ambitions. At the time, nurses did not receive proper training and nursing was not considered a suitable occupation for a woman of Florence’s status.

Her mother eventually changed her mind and between 1850 and 1851, Florence received basic nursing training in Kaiserworth, Germany. She was only allowed to attend for short stretches of time, however, and had to keep her education a secret.

By 1853, Florence freed herself from her restrictive family and, using her connections, took an unpaid position working in a nursing home for gentlewomen.

Crimean War

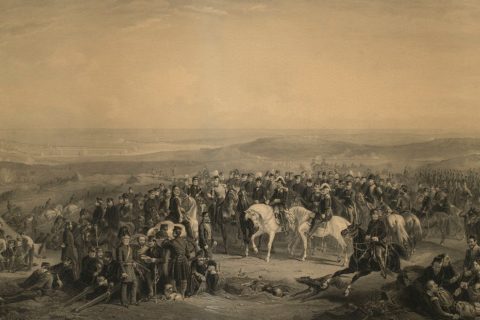

The Allied generals with the officers of their respective staffs before Sebastopol, mixed media engraving, 1859/©Royal Collection Trust, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

This engraving published in 1859 reproduces a history painting of 1856 documenting the Crimean War by Thomas Barker. It depicts a panoramic view of troops at Sebastopol, the largest city on the Crimean Peninsula. Florence made numerous trips to Sebastopol from her base at Scutari. In the engraving, she is identified in text (not visible) as one of the figures on horseback, checking soldiers with the Sanitary Commissioner.

In October of 1853 the Crimean War began, fought between the Russian Empire on one side and an alliance of British, French and Turkish Ottomans on the other. Newspapers regularly reported on the poor conditions and lack of medical care for soldiers.

In 1854, at the request of the British government, Florence went to Crimea. She led a group of nurses to Scutari, the site of a British hospital now in Istanbul. Her party was not welcomed by officers, however, and she quickly realised how bad conditions were, from insufficient supplies to dirty, overcrowded rooms. She even called the Barrack Hospital the ‘Kingdom of Hell.’

‘Lady with the Lamp’

19th-century plaster model of Florence Nightingale sitting on a bench and holding a lamp, an attribute for which she became famous/©National Trust

Under Florence’s watch, wards were properly cleaned and standards of care were established. This included attending to dressings and feeding and bathing soldiers regularly. She also recognised the need for psychological care and became known as the ‘Lady with the Lamp’, checking on patients at night.

Florence’s work was widely reported in the press at the time, shared through soldiers’ letters. She quickly gained fame and was credited with reducing the mortality rate in the Scutari Barracks Hospital to two per cent. Later, it was learned that the death rate was actually much higher than this, but the numbers had been doctored by the government.

A national heroine

Left: Florence in 1855, London Stereoscopic Company; Right: Florence in 1856 on her return from Scutari/©National Trust

By the time Florence returned home in August 1856 – seriously ill – she was an icon. The Victorians had a vibrant celebrity culture and active print media which was fanned by industrial advances in publishing and the invention of photography. Florence’s persona was particularly popular, with her often being represented as a ‘ministering angel’, mirroring common social impressions of women as selfless guardians and caretakers. Such was Florence’s celebrity status, that her signature is included in an autograph album belonging to Helen Leach, Beatrix Potter’s mother, alongside the likes of the Duke of Wellington, Robert Peel and even King George IV.

Many photographs of Florence were made, shared and collected, and Florence figurines, dolls and models were produced as popular objects. Examples of these are in the collections at Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire and Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd. The Staffordshire Pottery, known for making figures of famous people in the Victorian era, produced many different ‘Florences.’ These can be found at both Attingham Park, Shopshire and Newark Park, Gloucestershire showing the extent of their popularity.

Florence represented as a ministering angel, reflecting social impressions of women as selfless caretakers/©National Trust

Florence and nursing

A copy of “Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not” by Florence Nightingale at Claydon, Buckinghamshire/©National Trust

Florence did not enjoy her fame and was reluctant to be in the spotlight. Instead, she used her influence to campaign for better healthcare in England and to encourage public respect for nursing. Her efforts were high-profile, and she even met with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to champion the need for reform.

The Nightingale Fund, set up in 1855, raised money to open the Nightingale School of Nursing at St. Thomas’s Hospital, London, in 1860. St. Thomas’s is still an important hospital in the NHS landscape of today, and Nightingale’s nursing school taught skills that went on to form the basis of modern nursing as we know it.

In 1859, she published the book ‘Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not’, held in the collection at Claydon. This canonical work of nursing brought care principles into households across the country.

“Nursing is an art: and if it is to be an art, it requires as exclusive a devotion, as hard a preparation, as any painter’s or sculptor’s work”

In 1883, she was celebrated with dedicated Red Cross medals that show the long-term importance of her work.

Florence at Claydon

Florence Nightingale and Sir Harry Verney in 1880 in the grounds of Claydon, Buckinghamshire/©National Trust, John Bethell

Florence Nightingale has a special relationship with the National Trust. Her sister, Parthenope, married the English politician and soldier, Sir Harry Verney, of Claydon, Buckinghamshire in 1857. Florence visited them regularly and was later given rooms by Harry to work on her nursing books and hold important meetings.

Florence spent many years at Claydon, especially during the summer. Her rooms have been preserved and include numerous objects that belonged to her. Many of her possessions remain with the Verney family, including an orange she was given by a soldier in the Crimea and a lock of her hair.

Florence Nightingale’s room at Claydon, Buckinghamshire/©National Trust, Andreas Von Einsiedel

Florence’s legacy

Florence’s legacy still shines brightly, just like her lamp. Four hospitals in Istanbul are named after her, various care facilities in Derby pay tribute to her, and the new emergency hospitals that have opened in response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic have been named NHS Nightingale.

Florence also strongly influenced the essential status of the Red Cross, which can be seen in the armbands, ribbons, aprons, medals and letters found everywhere.

With the ongoing relevance of her nursing career now especially poignant, Florence Nightingale is not to be forgotten.