This blog continues in the “Europe & the U.S. in 99 Objects” series. Dr. Gabriella de la Rosa at the National Trust has started this project for the National Trust, originally published here, by delving into the Trust’s collections – nearly 1 million objects held at over 200 historic properties across the United Kingdom – to find objects with interesting, unusual and unexpected connections to Europe. These objects and their stories are being published in the form of a digital diary on the National Trust Collections website.

#26 The Excavations at Pompeii

Jakob Philipp Hackert (Prenzlau 1737 – San Piero di Careggi 1807)

Category: Art / Oil paintings

Date: 1799 (signed and dated)

Materials: Oil on canvas

Measurements: 1181 x 1638 mm (46 1/2 x 64 1/2 in)

Place of origin: Pompeii

Collection: Attingham Park, Shropshire (Accredited Museum)

On show at: Attingham Park, Shropshire, Midlands, National Trust

NT 608992

Caption

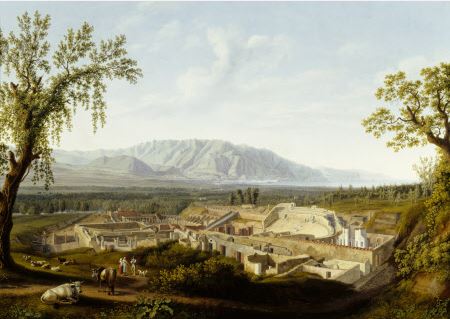

Real and imaginary depictions of ruins have been a staple of European painting since the Renaissance, so this painting by Jakob Philipp Hackert of an actual excavation would have been something of an innovation in 1799. It depicts one of the world’s greatest archaeological treasures, the Roman town of Pompeii, which was engulfed by ash from the devastating eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The large, open space in the centre is the theatre; to the left is the Triangular Forum and adjacent to it the Barracks of the Gladiators. On the right, behind its screening wall, is the best preserved and worst plundered of the shrines of Pompeii, the Temple of Isis. When Pompeii was rediscovered in the 1740s, interest focused on quarrying its art and artifacts. Many objects found their way into private collections while others were irreparably damaged or lost. Indeed, the excavations proceeded fitfully, unsystematically and unscientifically, and critics, including Sir William Hamilton, bemoaned the limited labor force and slow pace of work. Hackert’s picture certainly confirms this impression, where livestock outnumber people and the dry heat is almost palpable. In time, academies in Naples and Rome were established for the study of both Pompeii and Herculaneum and across Europe the ancient world was embraced within the arts, philosophy and science. Pompeii has since suffered more modern threats, from allied bombs in the Second World War, to degradation caused by heavy rainfall and hordes of tourists. Most recently, efforts to save the site from permanent collapse have been complicated by shoddy renovations and accusations of corruption and neglect.

Summary

Oil painting on canvas, The Excavations at Pompeii by Jakob Philipp Hackert (Prenzlau 1737 – San Piero di Careggi 1807), signed bottom right: Filippo Hackert dipinse 1799. A view to the south-west excavations at Pompeii, from higher ground, looking down upon the partially excavated ruins, with the Sorrentine peninsula in the distance. Companion to The Lake of Avernus. The artist probably finished the work in Pisa as he had to flee Naples during the Napoloeonic invasion and the pair were probably purchased during the peace of Amiens in 1802 by Thomas Berwick (rather than commissioned).

Full description

The view, looking toward Castellamare and the Sorrentine Peninsula, encompasses the excavated area of Pompeii as it appeared at the end of the 18th century. The large, open space in the centre is the Theatre, to the left is the triangular Forum and adjacent to it are the Barracks of the Gladiators and the Quadriporticus. At the extreme left is the Odeum or small theatre, and on the right, behind its screening wall, is the best preserved and worst plundered of the shrines of Pompeii, the Temple of Isis. Ever since Bulwer Lytton’s novel The Last Days of Pompeii (1834) gave dramatic form to – what had already been vividly presented in Pliny the Younger’s celebrated letters to Tacitus -the human tragedy of the engulfing of the town and its inhabitants by hot ash from the erupting Vesuvius in AD 79, and since excavations have laid so much of it bare, Pompeii has been the archaeological site par excellence, of which everyone has heard. Yet in the 18th century, when it was first discovered, this was not so. Then, it was overshadowed by its sister city, Herculaneum. This was partly because Herculaneum was discovered first -systematic excavations began in 1738 and continued vigorously until 1765, when the focus shifted to Pompeii and Stabia – but it was also because the initial interest of these buried cities was solely as a quarry for the extraction of Antique sculpture, wall-paintings, papyri, bronzes, and the like; and because the most spectacular finds of this type were made at Herculaneum. So much so, that murals found at Pompeii were first published in the volumes simply entitled Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte (1757-92). Then too, the fact that both sites were under royal control, and that Carlos III (1716 -1788), King of the Two Sicilies, and ultimately of Spain, forbade access to the excavations at Herculaneum to all but a very few, and would not allow visitors to the museum of excavated antiquities at Portici either to sketch or to make notes about the finds, whilst being very slow to have them published, gave Herculaneum in particular the aura of forbidden fruit. It was only later in the century, when the greater completeness of the survival of Pompeii allowed so much more of it to be brought to light and stand revealed (partly because of the manner of its destruction, by ash rather than lava, and partly because, being buried less deep, and without subsequent constructions over it, it could be laid bare by proper excavation, instead of being simply bored through by tunnels, as Herculaneum was), that interest in Pompeii began to equal that in Herculaneum. Beyond that, once the completeness of the survival of Pompeii had yielded plentiful evidence of where and how the Romans had actually lived, interest in this aspect of Antiquity began to overtake the earlier, spoliatory interest exclusively in works of art; whilst Fiorelli’s discovery in 1863 of the possibility of making plaster casts from the voids left by the trapped and fleeing figures gave the site a ghoulish fascination that has never left it . The Abbé de Saint-Non had included celebrated imaginary plates of the Discovery of Herculaneum and of the Transfer of the Antiquities of Herculaneum from the Museum of Portici to the Palazzo dei Vecchi Studi in Naples in his Voyage pittoresque, ou description des Royaumes de Naples et de Sicile (1781 -86), the material for which had been gathered in the 1770s, along with a dozen or so plates of the sites of Pompeii, together with others of plans and reconstructions of the main buildings, and of some of the objects found there . But the views of the sites, complete with elegant visitors, are of more picturesque than archaeological merit, in keeping with the slant of the whole publication. To paint actual excavations – as opposed to ruins – for their own sake was something novel, and in this – as in so many things -the pioneer would appear to have been Thomas Jones, in his oil-on-paper sketch of An Antique Building discovered in a Cava in the Villa Negroni at Rome in ye Year 1779 (Tate) . He had, however, to some extent been anticipated by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), who had made a number of visits to Herculaneum and Pompeii in the 1770s (how and under whose auspices does not seem to be known), recording his impressions of the sinister desolation of the sites of the latter, in particular, in a series of powerful drawings, some of which were later etched and published by his son Francesco in Les antiquités de la Grande Grèce – only, however, in 1804 -7 . Francesco had previously engraved seven detailed and more conventional drawings of Pompeii by Louis-Jean Desprez, which he published with a plan of the site in 1788 -89. It may have been these last – but also perhaps the visit to Italy in 1787 -88 of Goethe, for whom Hackert obtained permission to visit the museum at Portici and to whom he taught drawing, that inspired Hackert, who had not previously manifested any interest in portraying the excavations, despite his involvement with the museum at Portici, to paint a set of six gouaches of sites in Pompeii, and to have them engraved by his brother Georg. He announced them to his friend, Heinrich, Baron von Offenberg, in December 1792, as: “was Curioses Neues fürs Publicum von Europa” – showing that he recognised that, in the new order thrown up by the French Revolution, such excavations had become a matter of public interest, rather than simply the property of an individual ruler – though it was still only with the permission of Ferdinando IV that he could either paint them or have them engraved, finally publishing them in 1794 -96 . When this picture and its pendant were put up for sale in 1827, it was said that: “These Pictures were painted by order of the noble Proprietor”. Wegner therefore believes this picture to have been painted before March 1799, when the Hackert brothers, whose house had already been plundered by the Neapolitan lazzaroni, were forced to leave the Kingdom of Naples for that of Tuscany, by the withdrawal of the French troops who had, since their invasion, been guaranteeing law and order in the city. This is improbable, not least because the pendant, Lake Avernus with the Bay of Naples in the distance, is signed and dated 1800, and because the signatures on both are in Italian, whereas one of the other Hackerts at Attingham (probably from a group of paintings acquired by the 3rd Lord Berwick in Naples as late as 1827) is signed Philippe Hackert 1799 – no doubt because it was painted whilst Hackert was still in Naples, working under French protection. Thomas Noel Hill, 2nd Baron Berwick (1770 -1832) was back in England well before 1799, having made his grand tour of Italy in 1792 -94, with the Reverend Edward Clarke as his tutor, who had devised the subjects of two large pictures painted for him by Angelica Kauffman in 1793 -94, along with his portrait. It would, in theory, have been perfectly possible for Lord Berwick to have sent a commission to Hackert for this pair of pictures, but if he did do so, it would seem to have been the only case of his giving such a commission some years after his return. On the other hand, pictures on this scale were not of the kind to have been painted on spec, or for tourists, who would scarcely have come to Pisa to purchase such pictures anyway, even if it had not been for the French occupation of Italy. Furthermore, not only was it unusual to show Lake Avernus in its full Neapolitan context, rather than as a locus classicus, but this panoramic oil of Pompeii is also unique in Hackert’s surviving oeuvre (although a View of Pompeii was one of the nine pictures painted for King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia – six of them large-scale Views of the Environs of Naples, painted in 1795) – and installed in the Marmorpalais at Potsdam, that have been missing since World War II). It is very tempting to suggest that the present picture was begun as another royal commission, for Ferdinando IV, whose Court Painter he had been since 1786, and for whom he had painted (on the model of Vernet) a set of Views of the Ports of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1788 -92, and who had giv

en his permission for the publication of engravings of the six small gouaches of the Sites of Pompeii, yet apparently owned no depiction of it himself. Interrupted, perhaps, by the flight of the Court to Palermo in December 1798, before he had completed the picture, Hackert may have taken it to Pisa and then, in May 1800, to Florence, where he probably painted its pendant – having, perhaps through some intermediary, found the 2nd Lord Berwick as a buyer. In a letter that the 2nd Lord Berwick wrote to his equally indebted brother, the future 3rd Lord, in 1810, he admitted to not “having resolution to abstain from Building and Picture buying” as part of the explanation for the financial straits that he found himself in. He had, indeed, paid high prices for a number of pictures from the Orleans collection, including a purported Raphael of Saint John in the Wilderness for 1, 500 guineas and Titian’s Rape of Europa (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston) for 700 guineas; whilst he bought a Murillo Virgin and Child (Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York) from the Palace of Santiago in Madrid for £2, 500 . He had a splendid top-lit Picture Gallery added to Attingham by John Nash (who employed Pugin père to make the presentation gouache of his first design) in 1805-7. When the final crash came, it resulted in a two sales held at Phillips’s in London in 1825 and 1826/7, and in a 16-day sale of the contents of Attingham, held at the house by John Robins from 30 July 1827 onwards. Notes: This last auction did very badly, and a second sale held at the house in July/August 1829 did even worse. Three bought-in items from these sales, including Maso di San Friano’s Visitation (now on loan from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge to Trinity Hall chapel) and Thorvaldsen’s Shepherd Boy with a Dog (Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen), seem to have been detained or retained by Robins to sell on consignment, and were only finally sold at Christie’s, after Robin’s death, by order of the Court of Chancery in 1835. Some essential furniture, the family portraits, and 19 pictures -including this Hackert with its pendant and the pair of Angelica Kauffmans – were retained by the Hon. William Noel-Hill, future 3rd Baron Berwick (1773 -1842), who became the official tenant of Attingham, despite already owning, and in 1828 commissioning from T.F. Hunt designs for the rebuilding of, his own house, Redrice, near Andover in Hampshire, and although he was en poste in Italy, as Ambassador first to the Court of Sardinia (1808 -1824), and then to that of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1824 -33), to which his brother also retired. For him as a collector, and for the further shoals that this Hackert was to survive. (i) For the excavations of Herculaneum, see M. Ruggiero, Storia degli Scavi di Ercolano, Naples, 1885; and Fausto Zevi, ‘Gli scavi di Ercolano’, in exh. cat. Civiltà del’700 a Napoli, Naples, 1979 -80, vol.II, pp.58 -68. (ii) Voyage pittoresque, Paris, vols.I & II (1781 -1783). (iii) See exh. cat. Travels in Italy, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 1988, no.48. ( iv) See Hylton A. Thomas, ‘Piranesi and Pompeii’, Kunstmuseets Årsskrift, Copenhagen, vol.XXXIX -XLII (1952 -55), pp.13 -28. (v) See Brieven van Jakob Philipp Hackert an Johan Meerman uit de Jaren 1779 -1804, ed. Jos van Heel & Marion van Oudeheusden, The Hague, 1988, pp.36 -37; Reinhard Wegner,’Pompeij in Ansichten Jakob Philipp Hackerts’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgesichte, LXI (1992), pp.66 -96; do. & Wolfgang Krönig, Jakob Philipp Hackert, Cologne, 1994, pp.158 -59; exh. cat. German Printmaking in the Age of Goethe, British Museum, London, 1994, no.80. (vi) The Berwick archives contain an undated memorandum drawn up by a Mr B[archolz] and a Mr S[chmidchen], offering Mr. Hill [the later 3rd Lord Berwick] various picturs, including 2 large and 2 small Hackerts; and a letter from A. Schmidchen, dated as from 64 Sta. Lucia 13 May [18]27, with a furious annotation by Hill, objecting to the sundering of pendants, and saying: “I thought from first to last when the Pompeania were given up all the Hackaerts in oil were mine.” (vii) Berwick archives, Shropshire R.O., letter of 21 November 1810. (viii) See William Buchanan, Memoirs of Painting, 1824, vol.I, pp.47, 70, 81, 112 & 168; vol.II, pp.221 & 234. (adapted from author’s version/pre-publication, Alastair Laing, In Trust for the Nation, exh. cat., 1995)

Provenance

Probably commissioned by the King of Naples in 1797 for Thomas Noel Hill, 2nd Lord Berwick (1770-1832) after his visit and bought in 1802; his [bankcruptcy] sale, Robins (Warwick House, Regent Street), Attingham, 30 July ff. 1827, 6th day (6 Aug), lot 55 bought in at 52 gns by Tennant [possibly in competition with Mr Watson, John Soane’s agent, who had expressed interest in the pair as indicated in his catalogue of the sale] acting on behalf of William, later Lord Berwick (1772 – 1842), as one of the pair, together valued at £100 [whose accompanying note reads: “From the first to the last I have invariably said I wished to have the Hackerts and Denis’s if possible, the last words and continually repeated to Mr Smithkin were not to go upon a principle of division as it would be endless…”]; thence by descent; bequeathed to the National Trust with the estate, house and contents of Attingham by Thomas Henry Noel-Hill, 8th Baron Berwick (1877-1947) on 15th May 1953.

Credit line

Attingham Park, The Berwick Collection (The National Trust)

Marks and inscriptions

On front of canvas (bottom right): Filippo Hackert/ dipinse 1799 (signed and dated bottom right) and 56 On stretcher covered by modern backing board : ATT/P/056 On reverse of frame (top): National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C./ Exhibition: The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Patronage / Date: 11/3/85 – 3/16/86 Cat.185 / Artist: Hackert / Title: View of Pompeii / Lender: The National Trust. On reverse of frame (bottom): For Wildenstein Exhibition from Attingham Park On reverse of frame (bottom): Royal Academy of Arts Winter Exhibition 19 — (?) Artist: F. Hackert / Title: View of Pompeii / Name & Address of Owner: The National Trust (Attingham), 42 Queen Anne’s Gate. Ser. No.355, (pink chalk) ATT/P/056, (biro on label) J.P. Hackert, ruins of Pompeii, Attingham, Ex. No. 89 On reverse of frame (bottom): Wildenstein & Co., 147 New Bond Street / Exhibition … Souvenirs of the Grand Tour / Date .. 20 Oct. – 1 Dec., 1982 Cat. No. 31 / Artist… Jacob Philipp Hackert / Title .. Pompeii / Name & Address of Owner: National Trust, Attingham.

Makers and roles

Jakob Philipp Hackert (Prenzlau 1737 – San Piero di Careggi 1807), artist

Exhibition history

The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse and Resurrection , Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 2012 – 2013, no.54 The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse and Resurrection , The Getty Villa, Malibu, USA, 2012 – 2013, no.54 In Trust for the Nation, National Gallery, London, 1995 – 1996, no.31 The Treasure Houses of Britain, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA, 1985 – 1986, no.185 Souvenirs of the Grand Tour, Wildenstein, London, 1982, no.31

References

Wegner 1992 Reinhard Wegner, ‘Pompeji in Ansichten Jakob Philipp Hackerts’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Bd. LXI, 1992, Heft 1, pp.71, 72, 87-88 & fig. 18 Wegner and Krönig 1994 Reinhard Wegner & Wolfgang Krönig, Jakob Philipp Hackert, Cologne, 1994, pp.158 – 59 Nordhoff and Reimer 1994 C. Nordhoff and H. Reimer, Jakob Philipp Hackert 1737 – 1807 Verzeichnis seiner Werke, Berlin 1994 (2 vols.), I, p.181, pl.141, II pp.138-9, cat.no.286 Spinosa and Mauro 1993 Nicola Spinosa and Leonardo di Mauro, Vedute napoletane del Settecento, Naples, 1993, , p.200, no.148, fig.133

#27 Sissinghurst Castle with the Killing of a Group of French Prisoners

British (English) School

Category: Art / Drawings and watercolours

Date: circa 1761

Materials: Ink and dye on laid paper

Measurements: 545 x 765 mm

Place of origin: Sissinghurst

Collection: Sissinghurst Castle Garden, Kent (Accredited Museum)

On show at: Sissinghurst Castle Garden, Kent, London and South East, National Trust

NT 2900001

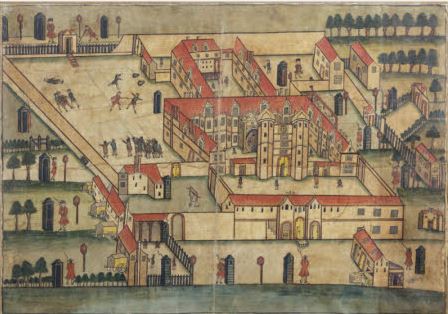

Caption

It’s one of the world’s most famous gardens, but the romantic ruined castle around which Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson created their horticultural refuge has a darker side to its history. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Sissinghurst became a prison where up to 3,000 French prisoners were incarcerated. French naval officers were housed in the tower where you can still see their graffiti on the walls. The lower ranks, however, were forced to live in squalid conditions and punished for petty crimes. It was a harsh place even by 18th-century standards. This naïvely painted picture records the fatal shooting of two compatriots by a drunken soldier of the Kent Militia, John Bramson. On 9 July 1761, Bramson loaded his musket with three balls and fired on a group of prisoners without warning. A prisoner later testified: ‘I was walking with the man Baslier Baillie who was killed in the garden. The sentry beyond the moat advanced two or three steps. He fired, and the man fell.’ Another ball hit Sebastien Billet, who is shown lying dead on the ground. In the general commotion, a further Frenchman was wounded by a militiaman with a bayonet, which is also depicted. The incident eventually led to an investigation of conditions for prisoners of war. Interestingly, the word ‘castle’ was only added to Sissinghurst’s name at around this time, as the prisoners called their place of incarceration the ‘château de Sissinghurst’.

Summary

Ink and dye on laid paper, Sissinghurst Castle with the Killing of a Group of French Prisoners, English School, circa 1761. Naive painting of Sissinghurst Castle in use as a prisoner-of-war camp, showing the killing of several French prisoners.