Today’s post orginally can be found here, by Dr. Gabriella de la Rosa

The return of the inlaid paneling to Sizergh Castle

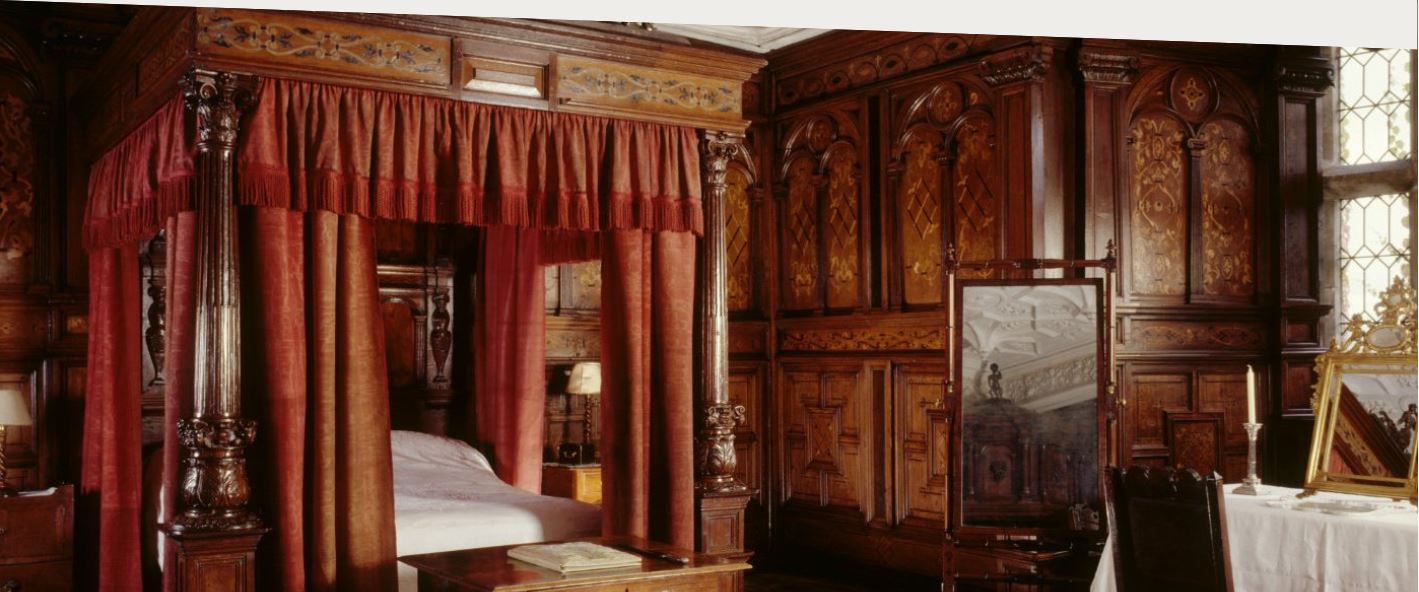

The Inlaid Chamber at Sizergh Castle, Cumbria. The magnificent Elizabethan panelling was installed in the late 1570s or early 1580s. © National Trust Images / Andreas von Einsiedel

Sizergh Castle in Cumbria is home to one of the finest examples of Elizabethan artistry, the magnificent Inlaid Chamber.

A rare masterpiece of heraldic stained glass windows, ornate plasterwork and elaborate inlaid panelling, it was a sign of the political aspirations and wealth of its original Tudor owners.

Yet despite its treasured status, it hasn’t been a permanent fixture at Sizergh. Discover the origins of this prized panelling, its removal in the 19th century and its eventual return in the 21st.

What is inlaid panelling?

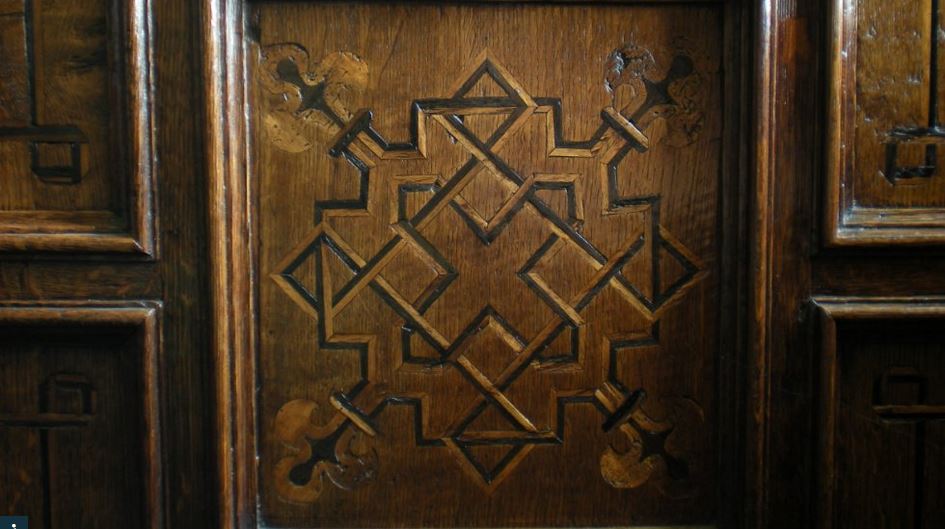

Inlay is the ornamentation of wood (in this case oak) by embedding cut-out pieces of a different type of wood (in this case bog oak and poplar) into the surface. The embedded pieces are used to create a pattern or motif in contrasting colours, flush with the surface.

The panelling in the chamber has been inlaid in the English manner, a painstaking and meticulous endeavour. By family tradition, this was the dedicated labour of one man and took his full seven-year apprenticeship to complete. So superior is the work, that the maker is thought to have been a master craftsman from Germany, where exuberant inlay techniques flourished.

Built to impress

Why was such an extravagant and expensive bed chamber created? The answer probably lies with the ambitious Thomas Boynton. Boynton was a rising political star in the 1570s. Elected MP in 1571, and made High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1576, he was knighted by Elizabeth I at Hampton Court and elected to serve on the Council in the North in 1577.

It is possible that a prospective visit from the Earl of Huntingdon – the president of the Council in the North and thus the Queen’s representative there – prompted Thomas Boynton and his wife to create the Inlaid Chamber, to ensure the comfort of such an elite guest, and to reflect the family’s increased status and wealth.

Hard times

This status and wealth did not endure, however. Two hundred and fifty years later, when another Walter Strickland inherited Sizergh, the family’s fortunes had fallen. Strickland was forced to sell furniture, paintings and the contents of an entire room, including the panelling from the Inlaid Chamber. Having been well-known for some years through reproductive engravings, the news that the panelling was for sale caused a flurry of interest.

The inlaid chamber was well known through reproductive prints such as this engraving after Thomas Allom in T. Rose, Westmorland, Cumberland, Durham and Northumberland, 1833 / NT 3033875

‘The most beautiful and most complete’

Despite this competition, and because they felt that the panelling was ‘the most beautiful and complete specimen of the English renaissance’ available, the Museum persevered. In 1890, for a sum of £1000, the panelling was removed to Gallery 52 of the West Wing of the South Kensington Museum.

In 1896 the Museum went on to purchase both the room’s impressive tester bed and the four heraldic stained glass roundels which hung in the window. For decades thereafter, the only reminders of the room’s former Elizabethan splendour were the heraldic plaster ceiling and an atmospheric engraving of the chamber by John Nash displayed on one of the walls.

For many years, an engraving hung on the stripped walls as a reminder of the room’s former splendour. From John Nash, Description of the Plates of the Mansions of England in the Olden Time (1849) / NT 3143399

Returned to its original home

The Stricklands first petitioned for the room’s return in 1949, and Country Life took up this call when the hall and its contents were presented by the family to the National Trust. Two sections of panelling were returned to Sizergh in 1973 and, owing to the re-organisation of the British Galleries at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the whole was returned on long-term loan to Sizergh in 1999, and the panelling finally restored to the room for which it was made.

Just this year, in 2016, in a gesture of great generosity on the part of the Victoria & Albert Museum, ownership of the panelling was officially transferred back to the National Trust. Today, the Inlaid Chamber, in all its panelled glory, is just as Sizergh’s owners, Thomas and Alice Boynton, envisaged it would be.