The University of Oxford and the National Trust are working together to create experiences that teach, move and inspire. University of Oxford historian and Royal Oak Lecturer Dr Oliver Cox recently introduced this partnership and we’re proud to share University students’ research in AngloFiles magazine. This week, discover the story behind the doll’s house at National Trust Uppark.

by Helena Kaznowska and Hazel Tubman

Since the beginning of 2015, we as researchers from the University of Oxford have been collaborating with the National Trust at Uppark in West Sussex to curate a new exhibition that brings one of Britain’s oldest and most important doll’s houses to life. The first part in a process we call ‘Story Intervention’ is coming to a close, in which we offer fresh interpretations of the property’s exquisite doll’s house and explain its multiple roles in early eighteenth-century domestic life.

Hazel and I are students of social and cultural history of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with a particular interest in the literature and life of the home. While this project enabled us to marvel at Uppark’s prize ornament for the first time, the doll’s house encapsulates our longstanding academic interests in miniature. Interestingly, the purpose of the collaboration between the University of Oxford and the Trust is decidedly not to further understand the object’s craftsmanship. After years of research by Uppark staff, local historians, academics and amateur enthusiasts, a great deal is known about the individual material features of the doll’s house, such as the decorative fabrics or types of paint applied. Little is known, however, about its actual use – and that’s where we come in.

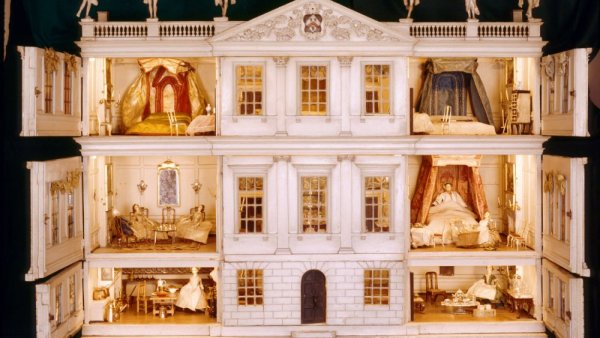

The doll’s house is stylistically distinct from Uppark itself and instead takes the form of a Palladian mansion, its central pediment painted with the Lethieullier coat of arms. It currently stands in the basement at Uppark in the Steward’s Hall, and although its original location is unknown, the ornate object almost certainly would have been on display in a grander room upstairs. Dating from between 1735 and ’40, the doll’s house is believed to have been brought to Uppark by Sarah Lethieullier when she married Sir Matthew Fetherstonhaugh in 1746. Lady Sarah was 24 when she moved into the property, which indicates that the doll’s house was originally an amusement for adults rather than a child’s toy for herself.

Why the doll’s house came to be at Uppark – whether it was a gift, part of an inheritance, or a commissioned piece by Lady Sarah – is unknown. Perhaps, you might wonder, the miniature was intended to entertain future generations of Fetherstonhaughs, especially since the couple’s son Henry was born in 1754? To go about answering this question, we need to examine the material evidence. The magnificent doll’s house is in excellent condition – suspiciously so. With such minimal damage caused over nearly three hundred years, it’s unlikely to ever have been regularly played with. The writer H. G. Wells, whose mother was the housekeeper at Uppark when he was a child, wrote in his 1909 novel Tono-Bungay that he ‘played discreetly’ with ‘the great doll’s house’ under ‘imperious direction.’ Clearly the pristine miniature wasn’t often touched by tiny hands or played with in a carefree manner.

Some Dutch and German doll’s houses dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were used as a tool for teaching. One example from Nuremberg, commissioned in 1631, was used by its enterprising owner as a business venture; women and girls, from mistresses to servants, would pay a small fee to behold the miniature home and incorporate it into their studies of domestic management. Scholars have attributed the same pedagogical purpose to eighteenth-century English doll’s houses – or ‘baby houses,’ as they were commonly known – as tools for young women to learn about the households they would inevitably oversee. This may well have been true for Lady Sarah, obtaining the object as a means of preparation for her forthcoming marriage and move to Uppark. But with her miniature’s emphasis on the handsome front of the house – and the servants’ sleeping quarters or washing areas excluded from the design – this example doesn’t offer a comprehensive model from which to learn about the management of a whole property and its staff.

Instead, the doll’s house could have emerged from the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century trend for creating cabinets of curiosities, which was, by and large, an indulgence of aristocratic gentlemen. Owners of doll’s houses could exhibit their most luxurious domestic goods in a miniature home comprising all their favourite rooms and in doing so create a female equivalent of the wunderkammer’s display of prized collectables. After all, the Uppark doll’s house is an ideal home rather than an embodiment of a practical dwelling. Owners of English doll’s houses such as Lady Sarah may have organised their miniature properties to form a personal container of memories, as its rooms highlight her individual taste through the assembly of old and new objects, and display a mixture of dated and fashionable domestic interiors. Some of the dolls inside, for example, wear late-seventeenth century fashions, while others in different rooms are dressed in garments typical of the mid-eighteenth century. Doll’s houses were domestic spaces that allowed for a freedom of expression, which might otherwise be difficult for women to convey within their life-size homes. In Uppark doll’s house, dreams of imagined interiors become a reality; the ornate object forms a collage of homes and homeliness, of personal memories and aspirational ideas.

What does this mean for the Uppark doll’s house exhibition? As researchers and curators, our aim is not to present a definitive explanation of what the doll’s house was used for, because it is clear that there was no single purpose. Instead, we want to devise a display that informs members of the public about our multiple theories of use and affords room for visitors’ own interpretations. The concept of miniatures holds the same fascination now as it did in the eighteenth century – think of Gulliver’s Travels, Thumbelina, Alice glugging from the ‘Drink Me’ potion bottles in Wonderland and, of course, the Borrowers – so we want visitors to freely imagine a wealth of possibilities for themselves. One way of doing this is to encourage participation within the exhibition by posing questions and welcoming commentary via interactive display boards. By asking members of the public two key questions – ‘Which rooms would you have inside your dream home?’ and ‘What do you think the doll’s house was used for?’ – visitors will be given the opportunity to share their own story, their own history, about Uppark doll’s house.

The initial research phase of the project is ending and now it’s time to determine the best way of exhibiting the Uppark doll’s house. The collaboration between the University of Oxford and the National Trust has been extremely rewarding, and we will continue to work together as we begin exchanging knowledge with the visiting public. We have shown the value of asking open-ended questions as we get closer to solving Uppark’s miniature mystery.