Many Royal Oak members will recall meeting journalist and historian, Tessa Boase, who traveled through the US revealing the stories she uncovered in her research about the upstairs, downstairs culture in Britain’s finest country estates. Tessa has agreed to share her stories here on Royal Oak’s online AngloFiles Magazine. If you’d like to learn more about Tessa’s research, you can purchase her book ‘The Housekeeper’s Tale’ here from her website.

The wheels at Downton Abbey have cranked forward a year. It is now 1925. And mutinous kitchen maid Daisy Mason – now assistant cook – is causing trouble, railing against ‘the system’, speaking her mind in places she shouldn’t.

Daisy’s plausible anger and frustration echoes that of another rebellious spirit, forced into domestic service in the Twenties.

Jean Rennie left Greenock High School at 17 with a scholarship to Glasgow University. But this was 1924 – the post war depression – and Ms Rennie, like thousands of others, was unemployed. So, as her mother before her, she ‘submitted to the badge of servitude’ – a cap and apron – with heavy heart, for £18 a year. She was an intelligent, ‘frightened and shy’ girl. Her mother was devastated. ‘I can see now the hurt in her eyes, that her eldest, gawky, clever, talented daughter, was going ‘into service’, as she herself had done at the age of 12 – without education.’

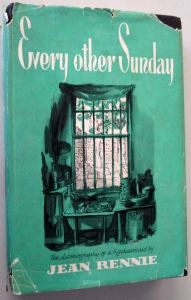

Jean worked her way up from scullery maid, to kitchen maid to cook-housekeeper. In 1955 she wrote a memoir, Every Other Sunday, in which she finally gave voice to her subversive thoughts and black humour. Jean was just the sort of servant the aristocracy feared: too observant, and too clever by half.

The rigid upstairs-downstairs hierarchies seemed absurd to her from the start. She describes the parlour maids as ‘scuttling round’ with brushes and dusters until the dinner gong went and they had to run. ‘Apparently we mustn’t be seen. It was to be assumed, I suppose, that the fairies had been at the room.’

We see, through Jean’s clear eyes, the upper class’s dirty laundry.

‘We toiled up the three flights of stairs again to the same bedrooms which we had tidied so nicely just over an hour before. It didn’t seem possible that one woman could make such a mess when all she had to do was step out of the clothes she was wearing, and scarcely needing to move, step into the other ones put ready for her. Drawers were open, powder was spilled lavishly all over the place, stockings, shoes, underwear, all flung anywhere. Margaret said nothing. I said plenty. But what was the use – we were “supposed” to do all this – we were paid for it; after all, “They” were “Gentry”…

At ten o’clock we took bottles up and put them in the beds. Curtains drawn, windows shut, hot-water bottles.

God Almighty! The joys of being rich!’

This memoir caused a small rumpus among the upper classes when published. Jean had flung those insistently instilled values – the idea that working for the aristocracy was a ‘nobility’ and ‘privilege’ – back in their faces. She exposes the pettiness, the whimsicality, the casual cruelty. But most usefully (and poignantly) she lets us know that servants have feelings too.

Jean Rennie managed, eventually, to leave domestic service, proudly earning herself a degree in her middle age (she wrote up the experience in Cap-and-Apron to Cap-and-Gown). Has Julian Fellowes read Jean’s two books? Will Daisy Mason escape from the basement of Downton Abbey by the end of the series, going on to enjoy some sort of personal fulfilment? As this is television, the answer is almost certainly yes. But if this were real life, I’m afraid she would probably have to wait another 14 years until WWII to make her escape – as Jean did.

by Tessa Boase