Not every aspect of housekeepers’ lives appears in Downton Abbey

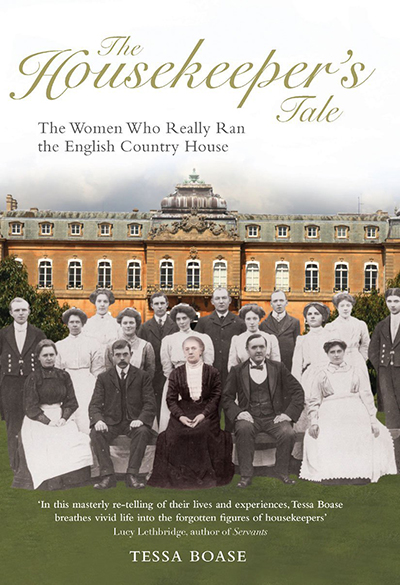

Journalist and author Tessa Boase knows her way around the English country house. She’s the author of the new book The Housekeeper’s Tale: The Women Who Really Ran the English Country House, which draws on entirely new sources to tell the extraordinary stories of the women who ran some of Britain’s most prominent households. Their lives, she discovers, were full of hard work and scandal, as Boase delves into tales of unwanted pregnancy, forbidden love affairs, prison sentences and several cases of summary dismissal.

In the course of her research, Boase has developed a keen eye for accuracy in modern-day depictions of Victorian country house life. While the most faithful shows, like Downton Abbey, go to great lengths to show life as it was at an English manor, they don’t capture absolutely every detail. Here are five parts of housekeepers’ lives that you never see depicted on the show.

Join Tessa for her upcoming Royal Oak lectures! Learn more

By Tessa Boase

1. Housemaids hiding from Lord Grantham

Lord Grantham wouldn’t have often been in the presence of housekeepers. Image courtesy of The Mirror.

Dressed in stiff aprons made of hurden (coarse, sacking like cloth), or a heavy grey drill-like cotton, pairs of housemaids would start cleaning rooms at 5am before the family was awake. If there was no electricity – and this was common in the grander houses – then it was done by candlelight. Rooms were re-cleaned throughout the day. As the family moved out of one, a small team of housemaids would move in to tidy it. When the bell signaling dressing for family dinner sounded, the maids waited for a few minutes before going into reception rooms to tidy up, check fires, blinds, plump cushions, remove dead flower petals…

One young parlourmaid, Jean Rennie, was astonished by this ritual at her first job in 1925. She described her team as ‘scuttling round’ with brushes and dusters until the dinner gong went and they had to run. ‘Apparently we mustn’t be seen. It was to be assumed, I suppose, that the fairies had been at the room.’

Some households were ruthless in their pursuit of the ‘invisible’ servant. At Crewe Hall in Cheshire, Lord Crewe’s strict orders were that housemaids who were seen by visitors should be instantly dismissed. At Woburn Abbey in the 1880s, any servant seen by the Duke of Bedford after 12pm was liable to instant dismissal. A generation later, even the electricians wiring the house used to bundle hurriedly into a cupboard when their lookout reported the Duke’s approach.

2. Phyllis Baxter saving the tea leaves

The Victorians were neurotic about dirt, in part because of the very real threat of disease. Best housekeeping practice in the big houses was passed down well into the mid 20th-century. Curtains, rugs, upholstery would be beaten by hand; wooden floors were dry-swept and dusted every day. Carpets were brushed on hands and knees at least twice a week. To prevent dust from flying about, all sorts of unexpected things were used – sand, wet tea leaves, damp salt, pepper, grass cuttings, shredded cabbage leaves, even dry snow – scattered over the surface and swept up with the dust.

Wooden surrounds to the carpets were polished with beeswax and a ‘donkey’ or a ‘jumbo’ – a solid stone block with a thick felt pad underneath and a long handle to push and pull it. The jumbo was a fiendishly heavy tool for a malnourished, sleep-deprived, teenaged housemaid to wield.

3. Mrs Hughes checking the dirt

Had the floor been swept properly by the housemaids? Experienced housekeepers had a unique way of finding out. Dust would be collected at specified points – near the door, in front of the fireplace – and the housekeeper would bend down to examine it. She knew exactly how big it should be, if the job had been done well. In smaller houses where there was no housekeeper, some neurotic mistresses insisted on weighing the dirt, to ensure their housemaid was cleaning properly. There were, of course, ways around this for the devious servant. One maid confessed to keeping a bag of dirt in her workbox expressly for this daily weighing ceremony.

4. Lady Mary stoking the fire

Six months of the British year were dominated by fire stoking, grate riddling, ash disposing. Life was a battle with damp and draughts. The fashionable rebuild at Highclere Castle (‘Downton Abbey’) was finished by 1878 – and it was a monument to Victorian standards of conspicuous inconvenience. This meant that it was prestigious to make absolutely no concessions to easy running. If coal had to come from an outside coalhouse, there was male staff to bring it in, and maids to put lumps on the fire when the bell was rung for them. No lady would stoop to picking up the tongs and putting one lump of coal on the fire herself. Certainly not Lady Mary.

Firelighting was an art: the experienced housemaid was expected to manage the task using no more than seven pieces of wood. Her efforts would be checked by housekeeper and butler.

5. Mrs Hughes whisking up bullock’s gal

The bright steel fireplaces, elegant features of many country houses, were a devil to keep clean. They had to be scoured with an abrasive powder (bath brick or emery) mixed with some sort of oil. One housemaid recalled how, in the 1920s, steel fire bars were rubbed with emery paper first, then with a burnisher, a small square of leather covered on one side with fine chain which burnished the steel until it looked like silver. Another way was to rub the steel vigorously with a large pebble.

After cleaning the fireplaces, the housemaid cleaned the hearths. Marble hearths were washed with soap and water and dried with a linen cloth, or cleaned with a frothy liquid made from bullock’s gall. Freestone hearths were scoured with soap, sand and cold water. Slate slabs were polished with hot mutton fat.

A maid at Thorpe Lubenham Hall in Leicestershire in the 1930s remembered starting on the grates at 5am. She had to be finished and cleared away by the time she took a cup of tea to the fierce housekeeper at 7am.

Don’t miss Tessa’s Royal Oak lectures, coming soon! Learn more