By Jeremy Musson, Architectural Historian

This article first appeared in the Fall 2014 Royal Oak Newsletter

As we near the anniversary of the Victoria & Albert Museum‘s landmark exhibition, “The Destruction of the Country House,” Royal Oak examines the country house, its continued survival and its connection to the political economy with architectural historian and frequent Royal Oak lecturer Jeremy Musson.

Support Royal Oak’s efforts to preserve the English country home. Donate today! Donate

Although we all revel in the entertainment of Downton Abbey and the seductive image of a country house in full rig, it is clear that the world of the country house in the twenty-first century is an immensely complex and layered one. There are country houses still attached to country estates and in private ownership and those vested in charitable trusts, or vested in the National Trust, and those in public ownership, either with English Heritage or, in the case of over hundred and fifty historic houses, owned as museums or heritage assets by local governmental authorities. This does not include the many listed country houses long in occupation as council offices, care homes, hospitals and the like, which are of course not accessible to the generally interested visitor, nor do they contain contents of interest.

Economic austerity has inevitably had an impact on all sectors, although it manifests itself in surprisingly different ways. As Norman Hudson, chairman of the Country Houses Foundation says: “when people have less to spend, they are more likely to holiday at home, and country houses offer such a lot for the visitor”. The National Trust has not been radically affected by economic austerity, the Trust’s chairman Simon Jenkins observes: “We saw some levelling off in commercial revenue round 2012 but membership and visits continue to climb. We get no public sector core funding. What has been noticeable has been the number of local authority properties in trouble.”

The historic houses in local authority ownership have been especially hard hit, with budget cuts from central government putting enormous pressure on all aspects of arts and heritage provision, and in a number of cases important country houses, have been threatened—for instance, a couple of years ago Manchester City Council effectively closed both 18th-century Heaton Hall and 16th-century Wythenshawe Hall. Heaton Hall was designed by James Wyatt and is one of the finest neo-classical country houses in England, listed Grade I.

Naturally, solutions are being sought: Wythenshawe Hall has re-opened its doors for two days a week and the National Trust is currently advising Manchester City Council on the development of a strategic framework for the Heaton Hall and its park. The Trust has also recently agreed to a 50-year lease of late-17thcentury Tredegar House near Monmouth which had been acquired by Newport Council in 1974. There are today many local authorities which are battling to preserve similar historic jewels, which – with their parks – are important cultural assets, against a sustained period of cuts in public funding. The Heritage Lottery Fund has played a key role in sustaining many of these—the recent restoration of Forty Hall in Middlesex is a case in point. Without the HLF’s £4.7 million support recently announced it is difficult to see that historic Gunnersbury Park could have had a viable future at all.

Country houses in private ownership have, according to Robert Parker of the Historic Houses Association, been reacting to the economic downturn by new levels of entrepreneurship. “Over the last decade there has been an even greater move to commercialisation, the pop concert, weddings and country fairs, even in houses which have not been regularly open to the traditional visiting public. At the same time I think the visiting public have become ever more discerning and demanding.”

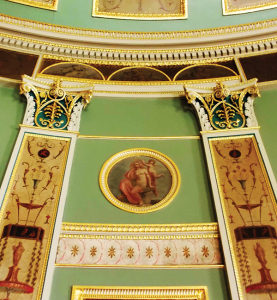

Heaton Hall’s spectacular neo-classical interiors were designed by James Wyatt. Phto courtesy of Colin Hepburn.

Commercialization is naturally desirable for revenue generation. However, it can present a challenge to occupied houses, with its related loss of privacy and even of character, which can be an issue especially for the next generation of owners or custodians. It is also clearly a great challenge for smaller charitable trusts which maintain many historic country houses of interest open to the public, especially those which have been ‘rescued’ from decay, because such commercialization requires major investment that is often beyond their reach.

Perhaps the greatest dangers posed by the recent economic crisis will only be properly understood in the future, namely the backlog of repairs that will have accrued during a sustained period of economic downturn. A recent survey by HHA, taken at the height of the recession in 2013, shows that the backlog of urgent repairs at privately owned historic houses had nearly doubled since 2009, and stood at something like £764m nationally (£390m in 2009 and £260m in 2003). The National Trust’s current restoration project at Castle Drogo is costed at £11 million and, while funding for those works has been secured, it is in itself evidence of the scale of costs involved in repairing major country houses.

This autumn the Victoria and Albert Museum marks 41 years since the famous Destruction of the Country House exhibition with a small special exhibition and a symposium. The curators of that exhibition were fighting chronic social and institutional indifference. During the 1980s and 1990s the scene was transformed with country houses being recognized as important heritage assets and tourist attractions—but without a sustained improvement in the economy, sooner rather than later, there could well be a few more battles ahead for custodians of Britain’s built heritage.