Part 1

By Sean E. Sawyer, Ph.D.

Former Executive Director of The Royal Oak Foundation

(Adapted from PowerPoint presentation to blog format by Jacqueline Bascetta)

Sean delivered a version of this post as a lecture for Royal Oak members around the country in the final months of his tenure as Royal Oak’s Executive Director. In it, he examines the National Trust’s role in securing the English country house and preserving these special places for generations to come. Help us continue the National Trust’s essential preservation work by contributing to our Furniture Appeal, benefiting research on one of the largest and finest collections in the world. Donate Now

At least 1,900 country houses were demolished in the United Kingdom in the course of the 20thC. Many were major historic properties, the time-honored seats of noble families as well as great works of architecture, embodying the historical consciousness of generations. Every one of them had stories to tell, often ones of such drama that the plot lines of “Downton Abbey” pale in comparison.

The rescue of the country house in the late 20thC is also a fabulous story and one that Royal Oak’s partner, the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland has played a principal role in. This five-part post series will discuss the role of the National Trust in the rescue of the country house and the role that Royal Oak and our supporters around the US play, but we shall start our discourse with a case study of a lost house and the historical reasons behind the crisis of the country house.

Part 1: Cassiobury and the Decline of the Country House

Cassiobury in Hertfordshire, just northwest of London, was an ancient house, whose dismembered remains are now spread across the United States. It was built in the reign of the Tudors, around 1550, by the Morrison family. Elizabeth Morrison married Arthur Capel, 1st Baron in 1627, bringing the estate to the Capels. The family was deeply enmeshed in the political turmoil of the mid-17thC and the Baron, an ardent Royalist, lost his head in 1649; but his true heart was put in a silver casket and presented to Charles II on the Restoration in 1660.

At this time his son, also named Arthur, was made Earl of Essex and had a high profile political career. He hired the architect Hugh May to reconstruct the crumbling Tudor Cassiobury, turning it into a Restoration era show house fit to receive the king.

However, the Earl became embroiled in the political dramas of his time and, facing charges of treason, he took his own life rather than risk having his estates taken from the family. After this drama, the Earls of Essex succeeded each other peacefully and with few notable accomplishments into the 19th century.

Beginning in 1800, the 5th Earl remade Cassiobury as a fashionable picturesque seat, commissioning James Wyatt to encase it in his “toy fort” Gothic Revival style but leaving the interiors largely intact. He hired Humphrey Repton to landscape the park, incorporating the Grand Union Canal as landscape feature.

However, this period of peace and plenty was short-lived. The Earls of Essex faced straightened circumstances with the agricultural crisis of the 1880s, and the first Christie’s sale of fine and decorative arts followed the death of the 6th Earl in 1893.

The 7th Earl got the message and by the end of the year had married his American Dollar Princess, Adela Grant, daughter of David Beach Grant and heiress to his Patterson, NJ locomotive making fortune. This was no Vanderbilt dowry, however, and when the 7th Earl was killed by a taxi in 1916, crushing inheritance taxes – death duties – forced the sale of the estate. There was a 10 day-long auction of contents and the house was offered with 870 acres of land. With the burgeoning suburbs of Watford encroaching, the land was much the more valuable entity, and the house was demolished in 1927 with its materials scattered to the winds, including 300 tons of oak, 100 fine beams, 10,000 Tudor bricks. The Gibbons carvings – the finest outside of Windsor or Hampton Court – were sold for £20,000 and scattered widely, from the V&A to Castle Hill, the Crane Estate, in Ispwich, Mass., where Gibbons’ over mantle and Wyatt’s bookcases are installed in the library.

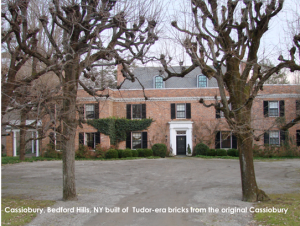

The magnificent carved staircase by Edward Pearce eventually found a place in New York’s Metropolitan Museum, and even the bricks set sail for the Big Apple,- – forming the facades of a new Cassiobury in Bedford Hills, NY, built in the late 1920s to designs of Harriet Meeker Cox Hooper, a designer and widow of Horace Hooper, owner of the Encyclopedia Britannica.Cassiobury is just 1 of the more than 1,900 country houses that were lost in Britain during the 20thC.

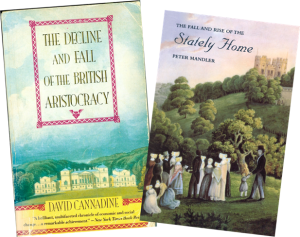

“The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy” by David Cannadine and “Stately Home” by Peter Mandler profoundly impacted Sean.

Of course, this is a story that has been told frequently, in many different media and from differing perspectives, over the past generation – – the two books that have most influenced my thinking are that by my doctoral advisor, David Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy, of 1990 and Peter Mandler’s The Fall and Rise of the Stately Home of 1999. Cannadine’s is the definitive text on the economic and political causes and effects of this epochal change in British society, while Mandler’s work is of particular importance for those of us interested in the significance of the country house in the modern world, especially as a tourist destination and emblem of Britishness.

Going around country houses today, you will often hear that they first opened to the public in the aftermath of WWII and only became objects of international fascination in the 1980s with Brideshead Revisited and the Treasure Houses exhibition at Washington’s National Gallery, however, Mandler demonstrates that the first country house tourism boom was in the mid-19thC with the advent of the railways and omnibus. We might not be surprised that Hampton Court had 200,000 visitors in 1850, but did you know that Chatsworth welcomed more than 50,000 visitors at this time? Indeed, the country house was much more accessible in 1850 than it was in 1950.

Moreover, it is crucial to understand that the country house is a residence at the center of a great estate, and it is the land – not the house or its collections – that was basis of economic wealth, political power, and social status.

What happened from the 1880s through the 1930s in Britain was a revolution in land ownership that has only been paralleled in British history by the Norman Conquest and the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII. The reasons for this major historical change will be discussed in the next post.