By Chelcey Berryhill, Development & Communications Coordinator

All of us at The Royal Oak Foundation are excited to launch our 2015 National Trust Appeal for the Furniture Research Project. For inspiration, I’ve been digging through the Royal Oak archives and boy did I find an article to whet the appetite of our furniture and decorative arts enthusiasts!

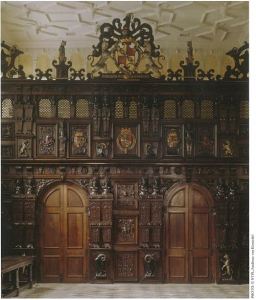

Interior of the west wing at Seaton Delaval Hall, Northumberland, built for Admiral George Delaval by Sir John Vanbrugh, between 1718 and 1728.

In the spring of 2010, Royal Oak published an article in the newsletter by Tim Knox, then Director of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London and former architectural historian and Head Curator at the National Trust. This in-depth article describes the English country house interiors inch by inch, from the plasterwork on the ceiling to the elaborate needle-work on the furniture.

I hope you enjoy reading this article as much as I did. Most importantly, I hope this confirms the significance of our 2015 National Trust Appeal for the Furniture Research Project. The National Trust cares for over 750,000 objects of fine and decorative arts and 350 historic homes – many of which are English country houses. With your help, the vast undocumented collections across the National Trust properties will come to life in an online, world-wide database for curators, historians, designers and artists to use in work and for inspiration. Support this project today and enjoy this article from our archives. Donate Now

The English Country House Interior by Tim Knox, from the publication The English Country House: From the Archives of Country Life

“The interiors of most English country houses are layered places, their contents and fittings reflecting the ebb and flow of the fortunes of their proprietors. However, in many houses it is still possible to find well-preserved interiors that are characteristic of their age. Thanks to decay and changes of fashion, no medieval country house retains an authentic interior even the most convincing ambiances in ancient manor houses are usually clever antiquarian confections. Much more survives from the 16th century, when prosperity and comparative peace and stability encouraged wealthy landowners to commission finely carved paneling and woodwork to decorate their country houses. Perhaps most impressive are the screens that dominate the great halls of houses such as Chastleton in Oxfordshire, extravagantly carved with half-understood Renaissance ornament, the motifs often derived from contemporary engravings. Carved chimneypieces, sometimes incorporating costly imported marbles, were combined with richly carved wainscot, which would have been originally painted and gilded. Linenfold paneling was itself intended to evoke the rich hangings that clothed the walls in wealthier houses, only the tapestries of which, along with some grander embroideries and bed hangings, survive today.

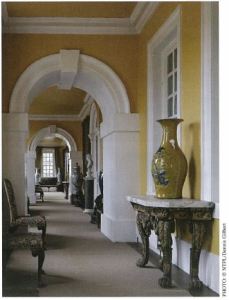

Elaborate plasterwork ceilings and friezes proclaimed the allegiances of their owners in a blaze of heraldry. In the 17th century, British country houses reflected the growing sophistication of architecture and the arts, with the importation of ideas and craftsmen from Italy and France. The magnificent interiors devised by the Frenchman Daniel Marot in the 1680s were imitated in the houses of the aristocracy and gentry, such as Belton House in Lincolnshire. Enfilades of lofty state rooms, lined with bolection-molded paneling of oak or walnut, or painted to resemble exotic woods, culminated in richly appointed closets hung with tapestry of Flemish, or sometimes English, manufacture, their bracketed overmantels teeming with blue and white china imported from Holland or the Orient. Virtuoso carvings by Grinling Gibbons and his disciples framed pictures and overmantels, while ceilings spored plaster birds, fruit, and flowers enmeshed within scrolling foliage — a motif echoed in the squirming contours of the fashionable gilded Sunderland picture frames. Upholstery again played a vital role in the decors, from the suites of mythological tapestries, to the elaborate needlework on beds and seat furniture.

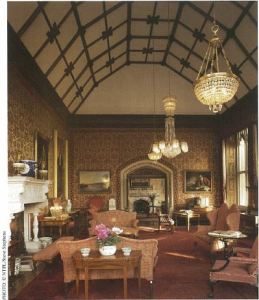

The Drawing Room at Tyntesfield with its barrel vaulted ceiling, looking toward the open doors to the Ante Room showing its ornate fireplace.

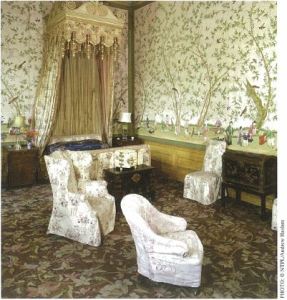

The 18th century saw a grand progression of styles in country house interiors. Experiments in the Continental Baroque championed by Vanbrugh and Gibbs were eclipsed in the 1720s and ‘30s by a cooler Palladian style, distilled from the treatises of Andrea Palladio under the 3rd Earl of Burlington and his followers. Burlington’s protege, William Kent, created interiors of great opulence that evoked the Italian palaces his patrons had seen on the Grand Tour, marshalling Old Master pictures and antique statuary in architectural arrangements against backdrops of damask or Genoese cut-velvet combined with monumental giltwood furniture. These, in turn, were overtaken by the lighter, prettier ornamentation of the Rococo and chinoiserie, seen in its most exaggerated form in the frenzied explosion of carved wood work at Claydon House, Buckinghamshire, or, more typically, rooms hung with Chinese painted wallpaper. 18th century Gothic — a fanciful evocation of medieval ornament as used in the interiors at Arbury Hall, Warwickshire — emphasized the antiquity of a family and recalled the glories of our native architectural tradition. But the classical style generally prevailed, reaching the height of splendor and refinement in Wyatt’s neoclassical interiors at Heaton Hall, Lancashire, or Adam’s Newby Hall in Yorkshire. Here, every detail, from the lock plates on the doors to the pattern of the carpet, is part of a harmonious decorative ensemble.

The wealth and prestige of regency and Victorian Britain is reflected in the country house interiors of the age. The neoclassical interiors devised by Henry Holland at Berrington Hall, Shropshire, and Southill, Bedfordshire, with their exquisite plasterwork and elegant furniture and upholstery, where eventually supplanted by spectacular displays such as Pugin’s brazenly confident polychrome and gilded library at Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire (c. 1849). Although the neoclassical or Rococo styles never entirely fell out of fashion — witness the opulent, club-like atmosphere that prevailed inside Brodsworth Hall in Yorkshire — such pagan or effete decors could hardly find favor with the pious merchant princes of the High Victorian era.

Houses like Tyntesfield in Somerset, or the Chanter’s House in Devon, had Gothic, almost ecclesiastical, interiors that reflected the tastes of their High Church proprietors, replete with polished marbles, stained and plate glass, encaustic tiles, and varnished oak, and fully equipped with all the latest technological advances.

It was partly a reaction against this brashness, and a nostalgia for the traditional arts and crafts of the Middle Ages, that led William Morris to carefully restore and furnish the run-down Kelmscott Manor in Gloucestershire for his own occupation. His doctrine of simplicity and utility was to inspire a whole generation of Edwardian architects and patrons, who created evocative, comfortable country houses like Blackwell in Cumbria and Great Dixter in Sussex.

Agricultural and economic depressions, two world wars, and dramatic changes in society made the story of the country house in the 20th century one of decline and retrenchment. However, despite the abandonment, sale, and demolition of countless great mansions, the public fascination with country houses has burgeoned, fueled by publications such as Country Life and the restoration and opening of houses by the National Trust, English Heritage, and dedicated private owners. Indeed, for every house lost, there were others being newly built, decorated, and furnished by the nouveaux riche like Sir Stephen Courtauld, who modishly restored Eltham Palace in 1933-36, or old grandees, such as the 16th Duke of Norfolk, who built Arundel Park, Sussex, after abandoning Arundel Castle in 1958. Revealingly, both of these new houses were classical, although the red brick “Wrenaissance” exterior at Eltham Palace, which collided shockingly with the surviving great hall of the Tudor palace, concealed a series of sleek interiors in the Swedish modern style.

The interiors at Arundel Park were entrusted to the fashion able London firm of Colefax and Fowler, and it was John Fowler, “the prince of interior decorators,” perhaps more than anyone else, who invented that comfortable mix of new and old furniture and textiles in an eclectic variety of historical styles known andimitated today as “the English country house style.” Fowler’s stylish and distinctive look can still be detected in very recent country house interiors, such as the pristine, Neo-Palladian Henbury Hall in Cheshire, and attests to the continuing vitality of the country house.”